Design principles

It seems like a no-brainer that when creating solutions for aging and longevity, we need specific, PEOPLE-informed design principles that can be used to guide innovation and decision making.

Let’s say mindset, creativity and flexibility are some of the most critical underpinnings required to fuel the development of solutions that make PEOPLE better, as I suggested in my previous post. Great, now what? That’s a rather vague set of aspirations to work from. I spent a significant part of my career as a designer, and one of the tools we use regularly are design principles. Design principles are essentially a set of guidelines that help you stay focused on the needs of the people you’re designing for. When done well, they’re an extremely helpful set of best practices that inform an entire organization’s decision-making approach.

During my time at PatientsLikeMe, Kim Goodwin worked with us and led the development of a set of design principles for our work supporting patients living with chronic diseases. One of the main goals of PatientsLikeMe was to enable every patient to learn from the experiences of every other patient who came before them, by turning their stories and experiences into data. We also offered many of the typical social features you’d expect in an online community. Designing for chronically ill patients requires a lot of thought and care. Being aware and respectful of their needs, goals, challenges and limitations was critical in order to make engaging with the site a useful, usable and valuable experience.

Here are the design principles we followed at PatientsLikeMe:

We exist to:

Get the data that makes a difference. We can’t change healthcare without it.

Help people achieve better outcomes by promoting informed decisions and actions.

Every patient wants us to:

See me as a whole person.

My doctors often don’t. That’s part of the problem. Let me manage my health, not just an illness. Don’t force me to compartmentalize (but let me do so if I wish to). Recognize that my biggest concern today may not be my biggest concern tomorrow.

Come with me on my journey.

In different times and places, I need different things. Provide clear guidance when something new is going on, but assume I master the basics over time. Be with me when & where I create and use information (doctor’s office, couch...often not at my desk). Help me capture things to discuss with my doctor as they come up (because I may not sit down and plan).

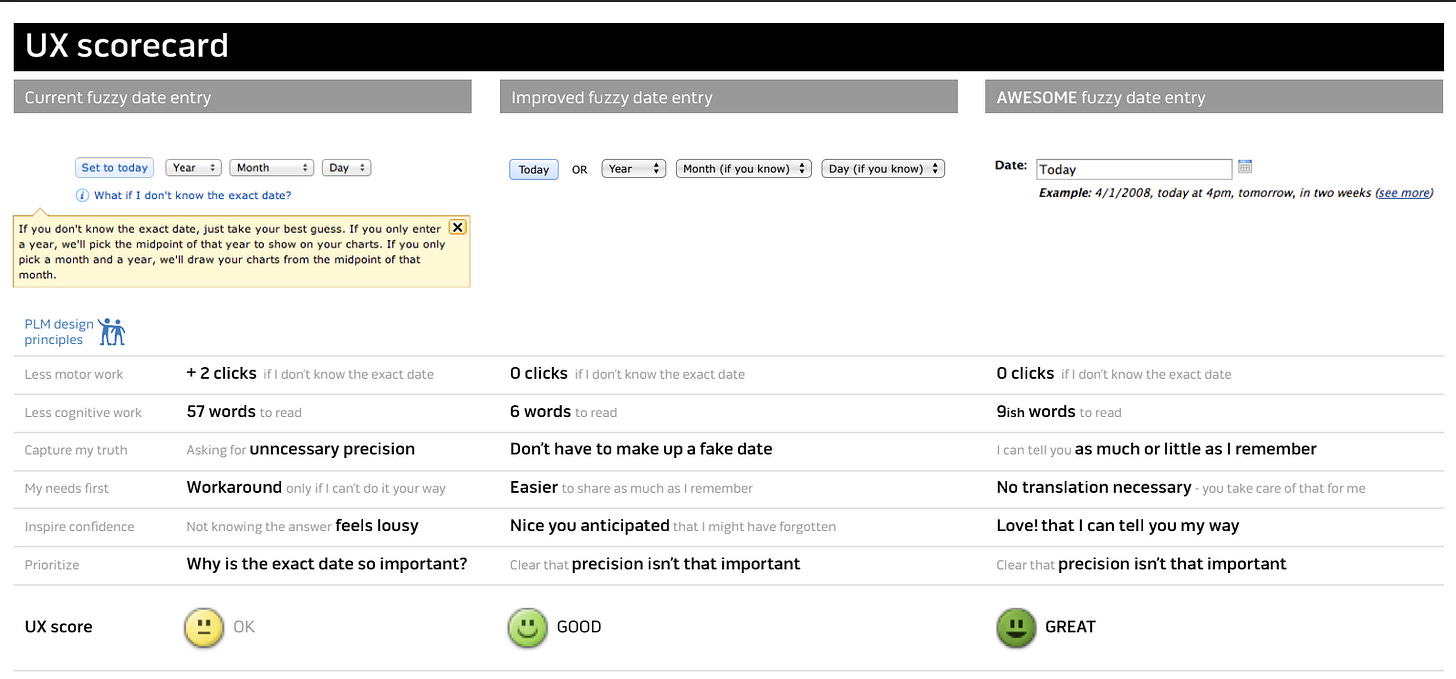

Help me capture my truth.

It bugs me if I can’t accurately reflect my own experience. Don’t ask me for unnecessary precision (my Advil dose or anything else no one will do research on). Don’t ask me to make up fake dates. If you want complete and accurate data, help me out (use name brands I recognize, remind me what condition sub-types are...).

Let me define who is like me.

Yes, show me efficacy based on genome, subtype, or other clinical factors, but that’s not enough. When I connect with people, I care about life stage, values, and life events as well as limitations, symptoms, stage & treatments. I’m also looking for people who share my experiences and values.

Help me feel in control.

Life feels out of control; I need to know I’m in charge. Let me enter incomplete data if I chose to, even if you can’t use it. Show me what I can DO to feel better or take a useful next step.

Put my needs first.

Address my needs before demanding I address yours. Tell & show me how I can change my health and help others. PLM isn’t changing healthcare by itself; we are doing it together. Assume I won’t answer carefully if you make me answer your questions first. Ask for help after my objective is met; I’m more likely to consider it then.

Inspire confidence.

Show me that PLM is worthy of my effort and trust. Give me helpful results (or point me elsewhere). Show me you understand what matters. Remember that every bug erodes my impression of you.

Build on what I already want to do.

I already spend time on my health, so take advantage of it. Extract data from things I’m already motivated to do: talk to my doctor, refill prescriptions, tell my story, take notes, track for understanding or tweaking, make & remember appointments, have my doctors know me, find information, get & give support.

Prioritize.

I have limited energy; show me where to put it. Draw my attention to the 1 or 2 most important things on every screen. Make sure every word, control, or pixel on the screen adds value. Don’t just show me data; show me meaning.

Minimize my work.

I may have dexterity, fatigue, cognitive, or memory challenges. Ask me the important stuff first; let me do the rest later. Be clear about the purpose of my effort. Don’t sacrifice legibility & ergonomics just to make it look cool.

Part of what made PatientsLikeMe’s design principles so strong is how tailored they were to the specific work we were doing and the population we were serving. More generalized design principles and heuristics also exist and are extremely helpful best practices to use if your aim is to create good design.

Given my experience at PatientsLikeMe and in many other contexts since then, it seems like a no-brainer that when creating solutions for aging and longevity, we need specific, PEOPLE-informed design principles that can be used to guide innovation and decision making. This set of principles, Gerontechnology: UX design principles for practical and engaging agetech solutions from the consulting firm ZS.com is a great start, but could definitely be expanded upon. As I work to extend and expand on theirs, and my own previous work, I hope you’ll chime in and share your experiences and learnings. After all, design principles are only helpful if they’re discussed, productively debated, and ultimately applied.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe to receive new posts if you like what you read. If you want to show your support, please react ❤️ comment 💬 or repost 🔁 . It’s an easy (& free!) way to be an ally and show support.

What I love about a set of well-defined principles like this is that it provides a framework for making decisions when the answer is not self-evident in the data. I.e. When presented with options about how to deliver a new feature one could ask “Which one helps me better ‘capture my truth’”? or “how can this experience ‘put my needs first’ in a better way?”. This is so helpful for keeping teams aligned to the intended spirit of the experience over time and as new people come and go.